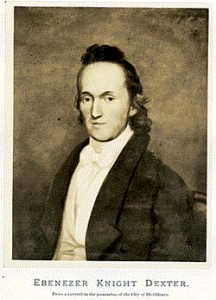

Dexter Donation: Ebenezer Knight Dexter’s Enduring Gift to Providence

Born in 1773, Ebenezer Knight Dexter entered adulthood at just the right moment to “become engaged in mercantile pursuits,” as described in a 1816 article in The Rhode-Island American entitled “Family Aristocracy.”[1] The small cluster of families controlling Rhode Island’s government and economy included most of Dexter’s relatives or close friends, with prominent names such as Fenner (a governor); Howells (district judge and senator); Brown; and Aldrich.

Born in 1773, Ebenezer Knight Dexter entered adulthood at just the right moment to “become engaged in mercantile pursuits,” as described in a 1816 article in The Rhode-Island American entitled “Family Aristocracy.”[1] The small cluster of families controlling Rhode Island’s government and economy included most of Dexter’s relatives or close friends, with prominent names such as Fenner (a governor); Howells (district judge and senator); Brown; and Aldrich.

Unsurprisingly, Ebenezer’s businesses succeeded — aided, no doubt, by the fact that he became the U.S. Marshal for Rhode Island (and thus presided over the sale of ships seized in Providence Harbor), served on bank boards, and sold real estate. A 1806 advertisement offers, “For Sale, by Ebenezer Knight Dexter, A Few Pipes of real Holland Gin, of excellent Quality; and a general Assortment of Groceries at Retail.”

With no surviving children, Ebenezer spread his bounty liberally among his relatives and friends through his 1824 will. Included was “John Greene, the colored man now in my employ, as a reward for his having continued in my service and to prevent him from coming to want, the sum of $60 yearly . . .” Ebenezer also left Greene a suit of clothes.

In the seventeenth paragraph of his lengthy will, Ebenezer made his most significant bequest: “Feeling a strong attachment to my native town, and an ardent desire to ameliorate the condition of the poor and to contribute to their comfort and relief, I give, grant and devise to the aforesaid Town of Providence . . . my Neck Farm . . . lying southerly of the Friends’ Yearly Meeting School estate, together with all the buildings thereon, to be appropriated to the accommodation and support of the poor. . . . ”

The Neck Farm, on Providence’s east side, consisted of thirty-nine acres with some farm buildings. Ebenezer’s will stipulated that “Said town shall, within 20 years after my decease, erect all around upon the exterior lines of said farm, leaving, however [,] suitable passageways into the same [,] a good permanent stone wall of at least three feet thick at the bottom and at least eight feet high, and to be placed upon a foundation made of small stones, and as thick as the bottom wall and sunk two feet into the ground. . . .” The rationale for this colossal wall wasn’t provided. Was it to protect the people outside from those within, or the reverse?

Ebenezer died in 1824 and the Town of Providence, then with a population under 12,000, had to finance some back-breaking labor. By the time the wall was completed eight years later, it was well over a mile long and had consumed 7,840 cords of 4 ft. x 4 ft. x 8 ft stone, costing the town $12,700. (Fortunately, stone was plentiful in Rhode Island; it was claimed that in some fields the hay was said to be “harvested with scissors.”)

At the time, however, the wall was secondary to the asylum — originally three stories high, and later enlarged with a mansard roof and dormers. (Although called an “asylum” throughout its history, “poorhouse” would be a more accurate description.) By 1829, the Dexter asylum housed a keeper (with an annual salary of $600) and ninety-three inmates. Major expenses were recorded for livestock, farming equipment, furniture, and medicine, but the farm showed an occasional small profit, depending on the weather.

Life at the Dexter Asylum

Early asylum records include hundreds of certificates of indenture, binding inmates for usually six to twelve months. From 1828 to 1844, indentures were required for inmates with no visible means of support. This British tradition of enforced servitude was common in New England and widely used for youths apprenticed to learn a trade — such as printing or blacksmithing — and for the poor. The indenture for Thomas Stanton is typical:

Early asylum records include hundreds of certificates of indenture, binding inmates for usually six to twelve months. From 1828 to 1844, indentures were required for inmates with no visible means of support. This British tradition of enforced servitude was common in New England and widely used for youths apprenticed to learn a trade — such as printing or blacksmithing — and for the poor. The indenture for Thomas Stanton is typical:

“This Indenture made and entered into this twenty-seventh day of August A.D. 1828 . . . Witnesseth that the said Overseer . . . does hereby set to work, and bind out to the said Gideon Palmer for the space of six months from the date hereof, Thomas Stanton, a person of color, a minor under the age of twenty-one years, now residing in said Providence, able of body, of no visible means of support, lives idly and neither uses nor exercises any ordinary or daily lawful trade of business to get his living by; during which time said Thomas shall faithfully serve the said Gideon in such employment as the said Gideon may direct in and about the house and upon the farm which he occupies and improves, and obey all his lawful commands . . . And the said Gideon does, on his part, hereby covenant … that he will for the work and service of the said Thomas, provide him suitable and comfortable board, lodging and clothing during the time he shall serve the said Gideon as aforesaid.” On September 2, 1828, Thomas Stanton “left without leave.”

Some of the 1828 “Rules and Regulations” provide a window into the world of the Dexter Asylum: “At the ringing of the bell, 10 minutes before each meal, everyone at work shall cease and be ready with clean hands and face; at the ringing of the second bell, to repair to the dining hall. Those not attending shall lose that meal unless they can render a satisfactory reason for their absence.” Half an hour was allotted for breakfast and supper and one hour for the midday dinner. The rules further state, “. . . those who are clamorous, quarrelsome or otherwise unruly shall be removed from the table and deprived of the next meal.”

There were strict rules against smoking in bed. Also, “No intercourse [interaction] whatever shall be allowed between the unmarried males and females of the house.” Permission was required to leave the farm, and those suspected of harboring “strong liquor or stolen property” were subject to search. The penalty for begging was three days in the asylum’s jail. The master and matron had extensive duties, such as inventories of numerous items, ringing the bell for various daily activities, and “attending to the security, proper management, and comfort of insane or deranged persons, lodged in the maniac cells. . . .” (Although probably a quarter of the patients suffered some degree of mental illness, there was no other place for them until the founding of Butler Hospital in 1847.)

While meals probably varied considerably with the season and success of crops, the food was not luxurious; as this menu from 1869 demonstrates:

Breakfasts: White bread, cheese, and coffee. On rare occasions, brown or Graham bread could be substituted for white, and cold meat for the cheese.

Suppers: White bread, butter, and tea. (Children received milk.) Twice a week there were treats: hasty pudding with molasses, and milk with tea.

Dinners:

Sunday: Baked beans or peas, pork, brown bread

Monday: Pork tongues or corned beef, white bread, vegetables

Tuesday: Irish stew or fish, vegetables, white bread

Wednesday: Soup, fresh meat, vegetables, white bread

Thursday: Stewed beans or peas and pork, brown bread, rice and molasses

Friday: Fresh or salt fish, potatoes, white bread

Saturday: Soup, fresh meat, vegetables, white bread

Changing circumstances

The influx of destitute Irish into Rhode Island in the mid- to late-nineteenth century began to tax the city’s coffers. In 1849, the Providence Town Council limited inmate capacity to 180. As the larger community grew, the asylum could not, so its role in caring for the local indigent population shrank over time.

As Providence’s fashionable East Side developed around the asylum, many new neighbors were not favorably inclined toward the institution. Southwest winds often wafted the smell of manure into the kitchens and bedrooms of nearby homes. Worst of all was the wall — high, bleak, extensive, and depressing, it must have been like living beside an ancient penitentiary. Residents tried to have the wall moved back from street corners, maintaining it obscured the view of merging automobile traffic (true), but it always reappeared again, just a few yards away, still tall, intimidating and foreboding. Of course, children loved it — you “weren’t anybody” until you’d walked its entire length — but many learned the truth about stone walls and poison ivy shortly after a triumphant circumnavigation of Dexter Asylum.

The end of Dexter Asylum

Eventually, the resident population of Dexter Asylum dwindled, as asylums waned and relief for the poor assumed new forms. After lengthy deliberations, the local Superior Court ruled that the City of Providence could ignore Ebenezer Knight Dexter’s will and auction his much-maligned poor farm, with proceeds appropriately directed toward the social welfare intended by Ebenezer’s will. Local politicians were overjoyed (but at least 182 Dexter heirs appeared with outstretched hands), and an auction was held in the Superior Court in 1957. Nearby Brown University was the high bidder, and after the building was demolished, the site became home to its athletic complex. Ebenezer Knight Dexter’s wall is about all that remains to remind us that this site once existed “to ameliorate the conditions of the poor.” A few new openings serve drivers and pedestrians, but the wall itself is still in good repair and the new “inmates” appear to be happy.

Ebenezer Knight Dexter’s bequest for the comfort and relief of the poor served Providence for 179 years in physical form and continues to benefit the city through a foundation established from the sale of Dexter Asylum. In addition, the sturdy wall that now encircles Brown University’s athletic fields stands as a lasting tribute to his generosity and foresight.

Note

1 “Family Aristocracy.” Rhode-Island American, April 2, 1816, p. 2.

Edwin M. Knights, MD, a retired pathologist, helped introduce ultramicro methods for clinical laboratories and worked with Ames Co. on diabetic testing. In 1996, he and George A. Fischer, PhD., founded Genesaver, which preserves DNA by lyophilization. His book, Harvesting Health from Your Family Tree, appears on NewEnglandAncestors.org. — And yes, he did walk “the wall” as a child in Providence.

Dexter Asylum Records

The voluminous records of the Dexter Asylum are preserved in the Rhode Island Historical Society’s Manuscripts Division. They are divided into six sections: inmates, correspondence, lawsuits, inventories, farm records, and financial records. Records most likely to interest family historians are found in the first three series.

• Series 1: Inmates (1828 to 1957): cover records of admission, discharge, transferal or death, and life within the asylum. Some records include age, race, occupation (or lack thereof), and reasons for admittance.

• Series 2: Correspondence: Mostly business-related but also letters relating to inmates’ illnesses or deaths.

• Series 3: Lawsuits: Data on Dexter and related families collected during legal attempts to break Ebenezer Dexter’s will.

• The Rhode Island Historical Society requests that researchers interested in examining the Dexter collection (twenty-seven linear feet) contact its Manuscripts Division prior to their visit.

For more information:

- Rhode Island Historical Society Library, 121 Hope St., Providence RI 02906; 401-273-8107

- A summary of Rhode Island poor farm/asylum records prepared by Bob Sherman – www.poorhousestory.com/RI_PoorHouse_Report.htm

- www.poorhousestory.com: a clearinghouse for information about nineteenth-century American poorhouses.

- Smith, John. “Mr. Dexter and His Farm.” Brown Alumni Monthly (1963), 17.

- S. C. Newman, Dexter genealogy: being a record of the families descending from Rev. Gregory Dexter (Providence: A.C. Greene, 1859).